Early Beginnings of Anamorphic Art

Anamorphic art is a fascination visual technique, and mathematics to distorts an image in such a way that it can only be correctly viewed from a mirrored cylinder. It plays with perspective and optical illusions, challenging the viewer’s perception.

The origins of anamorphic art can be traced back to the early Renaissance period in Europe when artists began exploring the rules of perspective. This exploration was driven by a deeper understanding of geometry and mathematics, which influenced how artists could manipulate space and perception on a flat surface.

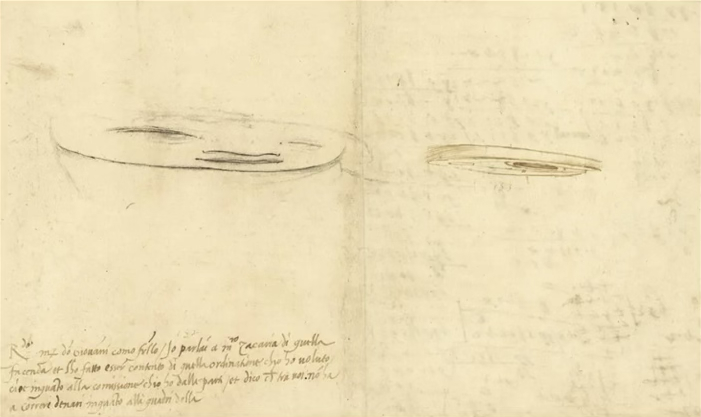

15th Century – Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci is one of the earliest known artists to experiment with anamorphosis. In his notes, da Vinci outlined the principles of distorted perspective, making him pioneer in the field. Here is one of the only surviving anamorphic drawings that da Vinci experimented with. His explorations laid the groundwork of future artists.

By 1750 anamorphic art was widely known and practiced among artists and scholars all over Europe. Among the anamorphic artists were Durer in Germany, Samuel Hoogstraten and Hans Holbein in Holland, Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Carracci, Vignola, Serlio and Barbaro in Italy, Mersenne, Descarte, Nicerlon and Maignon in France.

In the east, China had their own tradition of mirrored anamorphosis that flourished during the Wan- Li period [1573-1609]. Some art historians believe that Chinese anamorphic dates back to the Ming Dynasty [1368 -1644 ]. Mirrors have always held a formidable power in China.

Cylindrical mirrored anamorphic art emerged in 1751 and the effect was electrifying – the realistic image seemed to leap from the canvas on to the reflector. Collectors of cylindrical anamorphics were intrigued by its mystery. It seemed to reveal the fundamental aspects of nature and life.

However, according to the 1976 Rijks Museum catalog – anamorphic art reached its zenith in the 18th-century and vanished from the art world. Why did this intriguing, ingenious art disappear after four hundred years of investigation and experimentation leaving behind only a few examples? Did Providence play a role in its disappearance? Why did it remain largely unknown and then re-emerge forcibly almost 2 centuries later? Had it not fulfilled its role? Was it to continue its enigmatic evolution into the 21st century?

In the late 1970s, two Dutch men, Joost Elffers and Michael Schuyt, embarked on a five-year journey to rediscover anamorphic art, a technique that had all but disappeared since the late 17th century. Their search culminated in a groundbreaking exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 1976, the first of its kind. That same year, a young Indian artist, Shereen Miller, began her own quest to explore this mysterious art form, unaware that it would transform her life forever.

As she traveled across Europe, Asia, and America, Shereen found that anamorphic art was virtually unknown. There were no academic programs, no mentors, and no resources available to help her understand or create this intricate art form. There were no books, no art shops with the necessary reflective cylinders, and no guides to follow. Yet, despite the overwhelming challenges, Shereen was determined to revive this forgotten technique. Through a process of relentless experimentation and sheer creativity, she slowly began to unlock its secrets.

20th Century

In 1976, almost two centuries after the technique’s decline, Shereen Miller became the first modern exponent of anamorphic art in the 20th and 21st centuries. Her work not only rekindled interest in this ancient form but also expanded its possibilities, influencing how it could be appreciated in a contemporary context. Shereen’s cylindrical anamorphics bridged the gap between the lost centuries, reviving anamorphic portraiture and creating the first two anamorphic abstract pieces in the history of the genre.

Shereen’s pioneering achievements were all the more remarkable given the lack of resources or widespread knowledge about anamorphic art at the time. As the first woman to explore and paint in this technique, she had no mentors to guide her, no predecessors to follow, and no support from the broader art world. Yet, her innovative spirit and determination led to a profound revival of the form, making her a trailblazer in the process.

By 1988, twelve years after Shereen began her solitary exploration, the first English-language book on anamorphic art was published. But by then, Shereen had already made her indelible mark on the art world, demonstrating that even in the face of obscurity, a lost art form could be resurrected and transformed for future generations.

George Hersey, Yale University Art History professor, applauds Shereen Miller’s anamorphic art as extraordinary. Indeed, according to Hersey, Miller possibly stands alone in her exploration of this form. “She’s the only one I know of who does this”, Hersey says. She has taken this rather arcane speciality of anamorphism, which was cultivated by students of optics in the Renaissance and made it into a contemporary art form. That’s an innovation”!